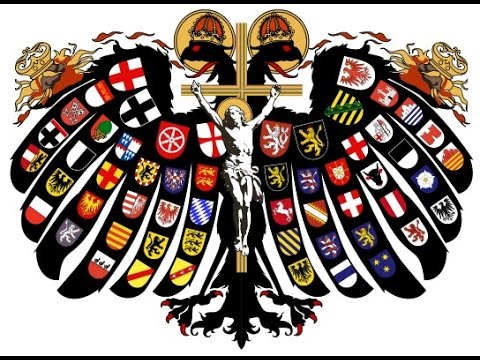

THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

The emperor generally dominated the various states and principalities that made up the German nation (which included present-day Austria, the Czech Republic, part of Poland, Luxembourg, and other bordering areas) as well as northern Italy. The emperor was chosen by electors representing certain states and dioceses, but the position tended to become hereditary, as the electors usually selected the ruler's natural heir. He customarily was crowned emperor by the pope in Rome.

Holy Roman Empire flag. The Holy Roman Empire flag flew in what is now Germany from the 1200's until 1806. It features a large beagle on a yellow background.

The emperor's power depended largely on his personal and family inheritances, and on alliances. Charles V, for example, when elected emperor in 1519, was also king of Spain and his domain included the Netherlands, Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, and Spanish America. His son, Philip, was the husband of the ruling queen of England (Mary I). Charles gave Austria to his brother Ferdinand, who was also king of Bohemia and of Hungary and succeeded him as emperor. Spain, however, went to his son, who became Philip II of Spain.

Background

T he Holy Roman Empire was an attempt to revive the Western Roman Empire, whose legal and political structure deteriorated during the 5th and 6th centuries, to be replaced by independent kingdoms ruled by Germanic nobles. The Roman imperial office was vacant after the deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476. During the turbulent early Middle Ages the traditional concept of a temporal realm coextensive with the spiritual realm of the church had been kept alive by the popes in Rome. The Byzantine Empire, which controlled the provinces of the Eastern Roman Empire from its capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey), retained nominal sovereignty over the territories formerly controlled by the Western Empire, and many of the Germanic tribes that had seized these territories formally, recognized the Byzantine emperor as overlord. Partly because of this and also for other reasons, including dependence on Byzantine protection against the Lombards, the popes also recognized the sovereignty of the Eastern Empire for an extended period after the enforced abdication of Romulus Augustulus.

he Holy Roman Empire was an attempt to revive the Western Roman Empire, whose legal and political structure deteriorated during the 5th and 6th centuries, to be replaced by independent kingdoms ruled by Germanic nobles. The Roman imperial office was vacant after the deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476. During the turbulent early Middle Ages the traditional concept of a temporal realm coextensive with the spiritual realm of the church had been kept alive by the popes in Rome. The Byzantine Empire, which controlled the provinces of the Eastern Roman Empire from its capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey), retained nominal sovereignty over the territories formerly controlled by the Western Empire, and many of the Germanic tribes that had seized these territories formally, recognized the Byzantine emperor as overlord. Partly because of this and also for other reasons, including dependence on Byzantine protection against the Lombards, the popes also recognized the sovereignty of the Eastern Empire for an extended period after the enforced abdication of Romulus Augustulus.

Romulus Augustus (fl. 461/463 – after 476, before 488), was the last Western Roman Emperor, reigning from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. His deposition by Odoacer (Flavius Odoacer (433–493, also known as Flavius Odovacer, was the 5th-century King of Italy, whose reign is commonly seen as marking the end of the classical Roman Empire. He is considered the first non-Roman to ever have ruled all of Italy). Traditionally marks the end of the Western Roman Empire, the fall of ancient Rome, and the beginning of the Middle Ages in Western Europe.

He is also known by his nickname "Romulus Augustulus", though he ruled officially as Romulus Augustus. The Latin suffix -ulus is a diminutive; hence,Augustulus effectively means "Little Augustus". Some Greek writers even went so far as to corrupt his name sarcastically into "Momylos", or "little disgrace".

The historical record contains few details of Romulus' life. He was installed as emperor by his father Orestes (died 28 August AD 476, was a Roman general and politician, who was briefly in control of the Western Roman Empire in 475–6), the Magister militum (master of soldiers) of the Roman army after deposing the previous emperor Julius Nepos (c. 430 – 480 was Western Roman Emperor de facto from 474 to 475 and de jure until 480). Romulus, little more than a child, acted as a figurehead for his father's rule. Reigning for only ten months, Romulus was then deposed by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer (433–493, also known as Flavius Odovacer, was the 5th-century King of Italy), and sent to live in the Castellum Lucullanum (Castel dell`Ovo) in Campania, a southern region of Italy; afterwards he disappears from the historical record.

(Romulus Augustus resigns the Crown)

After the abdication.

Romulus' ultimate fate is unknown. TheAnonymus Valesianus wrote that Odoacer, "taking pity on his youth", spared Romulus' life and granted him an annual pension of 6,000 solidi, gold coins, before sending him to live with relatives in Campania.

The sources do agree that Romulus took up residence in the Lucullan Villa an ancient castle originally built by Lucullus in Campania. From here, contemporary histories fall silent. In the History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon notes that the disciples of Saint Severinus of Noricum (ca. 410-482 is a Roman Catholic Roman saint, known as the "Apostle to Noricum) were invited by a "Neapolitan lady" to bring his body to the villa in 488, "in the place of Augustulus, who was probably no more."The villa was converted into a monastery before 500 to hold the saint's remains.

Cassiodorus, then a secretary to Theodoric the Great, wrote a letter to a "Romulus" in 507 confirming a pension. Thomas Hodgkin, a translator of Cassiodorus' works, wrote in 1886 that it was "surely possible" the Romulus in the letter was the same person as the last western emperor.The letter would match the description of Odoacer's coup in the Anonymus Valesianus, and Romulus could have been alive in the early sixth century. But Cassiodorus does not supply any details about his correspondent or the size and nature of his pension, and Jordanes, whose history of the period abridges an earlier work by Cassiodorus, makes no mention of a pension.

Last Emperor

As Romulus was a usurper, Julius Nepos was claimed to legally hold the title of emperor when Odoacer took power. However few of Nepos' contemporaries were willing to support his cause after he fled Italy. Some historians regard Julius Nepos, who ruled in Dalmatia until being murdered in 480, as the last lawful Western Roman Emperor.

Following Odoacer's coup, the Roman Senate Roman sent a letter to Zeno, who was Eastern Roman Byzantine Emperor from 474 to 475 and again from 476 to 491, saying that "the majesty of a sole monarch is sufficient to pervade and protect, at the same time, both the East and the West". While Zeno told the Senate that Nepos was their lawful sovereign, he did not press the point, and accepted the imperial insignia brought to him by the Senate

Growing Tensions

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 475 A.D., the Lombard tribe in northern Italy frequently encroached on lands held by the pope. In 753–54 Pope Stephen II traveled to Germany to appeal for help from Pepin the Short, king of the Franks. Pepin subdued the Lombards and declared the pope ruler of all church property holdings in Italy. The Lombards, however, continued to be a threat to the popes. Pepin's son, Charlemagne, made a number of expeditions to Italy to protect papal interests.

With the coalescence of the Germanic tribes into independent Christian kingdoms during the 6th and 7th centuries, the political authority of the Byzantine emperors became practically nonexistent in the West. The spiritual influence of the western division of the church expanded simultaneously, in particular during the pontificate (590-604) of Gregory I. As the political prestige of the Byzantine Empire declined, the papacy grew increasingly resentful of interference by secular and ecclesiastical authorities at Constantinople in the affairs and practices of the Western church. The consequent feud between the two divisions of the church attained critical proportions during the reign (717-41) of the Byzantine Emperor Leo III, who sought to abolish the use of images in Christian ceremonies.

Papal resistance to Leo's decrees culminated (730-32) in a rupture with Constantinople. After severance of its ties with the Byzantine Empire, the papacy nourished dreams of a revivified Western Empire. Some of the popes weighed the possibility of launching such an enterprise and assuming the leadership of the projected state.

The Lombard tribe in northern Italy frequently encroached on lands held by the pope. In 753–54 Pope Stephen II traveled to Germany to appeal for help from Pepin the Short, king of the Franks. Pepin subdued the Lombards and declared the pope ruler of all church property holdings in Italy. The Lombards, however, continued to be a threat to the popes. Pepin's son, Charlemagne, made a number of expeditions to Italy to protect papal interests.

Lacking any military force or practical administration, and in great danger from hostile Lombards in Italy, the church hierarchy, abandoning the idea of a joint spiritual and temporal realm, seemed to have decided to confer imperial status on the then dominant western European power, the kingdom of the Franks. Several of the Frankish rulers had already demonstrated their fidelity to the church, and Charlemagne, who ascended the Frankish throne in 768, had displayed ample qualifications for the exalted office, notably by the conquest of Lombardy in 773 and by the expansion of his dominions to imperial proportions.

The Western Empire

Holy Roman Emperor: AD 800

In 799, for the third time in half a century, a pope is in need of help from the Frankish king. After being physically attacked by his enemies in the streets of Rome (their stated intention is to blind him and cut out his tongue, to make him incapable of office), Leo III makes his way through the Alps to visit Charlemagne at Paderborn.

It is not known what is agreed, but Charlemagne travels to Rome in 800 to support the pope. In a ceremony in St Peter's, on Christmas Day, Leo is due to anoint Charlemagne's son as his heir. But unexpectedly (it is maintained), as Charlemagne rises from prayer, the pope places a crown on his head and acclaims him emperor.

Charlemagne expresses displeasure but accepts the honor. The displeasure is probably diplomatic, for the legal emperor is undoubtedly the one in Constantinople. Nevertheless this public alliance between the pope and the ruler of a confederation of Germanic tribes now reflects the reality of political power in the west. And it launches the concept of the new Holy Roman Empire which will play an important role throughout the Middle Ages.

Charlemagne expresses displeasure but accepts the honor. The displeasure is probably diplomatic, for the legal emperor is undoubtedly the one in Constantinople. Nevertheless this public alliance between the pope and the ruler of a confederation of Germanic tribes now reflects the reality of political power in the west. And it launches the concept of the new Holy Roman Empire which will play an important role throughout the Middle Ages.

The Holy Roman Empire only becomes formally established in the next century. But it is implicit in the title adopted by Charlemagne in 800: 'Charles, Most Serene Augustus, crowned by God, great and pacific emperor, governing the Roman Empire.'

On December 25, 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Emperor. When Pope Leo III placed the crown on the head of Charlemagne in St. Peter's, and the assembled multitudes shouted "Carolo Augusto, a Deo coronato magno et pacifico imperatori, vita et victoria!" — "To Charles the Magnificent, crowned the great and peace-giving emperor by God, life and victory!" Strictly speaking, however, Charles's empire was neither Roman nor German, but Frankish — or as we might say, a sort of French-German mix (for that matter, there was a perfectly valid Roman Emperor at the time in any case). The Empire was not officially described as "Holy" until the twelfth century, nor officially "German" before the fifteenth. Charlemagne's empire quickly fell to pieces among his squabbling successors, and the Holy Roman Emperors themselves tended to ignore any discontinuity between pagan and Christian Rome — Frederick I Barbarossa (1123-1190) going so far as to assert that one of his reasons for going on Crusade was to avenge the defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus by the Parthians. Marcus Licinius Crassus (Latin: M-Licinivs-P-F-P-N-Crassvs). ca. 115 BC – 53 BC, was a Roman General and politician who commanded the left wing of Sulla's army at the Battle of the Colline Gate, suppressed the slave revolt slave led by Spartacus, provided political and financial support to Julius Caesar and entered into the political alliance known as the First Triumvirate with Pompey and Caesar.

However, Charlemagne's empire was divided among three of his grandsons by the Treaty of Verdun (843) and soon broke into numerous feudal states that resisted the authority of the monarchs. Charlemagne's descendants enjoyed the honorary title of emperor. This act established both a precedent and a political structure that were destined to figure decisively in the affairs of central Europe.

The precedent established the papal claim to the right to select, crown, and even depose emperors that was asserted, at least in theory, for nearly 700 years. In its primary stage, the resurrected Western Empire endured as an effective political entity for less than 25 years after the death of Charlemagne in 814. The reign of his son and successor, Louis I, was marked by feudal and fratricidal strife that climaxed in 843 in partition of the empire. For an account of the growth, vicissitudes, and final dissolution of the Frankish realm, see FRANCE.

Emperors and Popes: AD 962-1250

The imperial role accorded by the pope to Charlemagne in 800 is handed on in increasingly desultory fashion during the 9th century. From 924 it falls into abeyance. But in 962 a pope once again needs help against his Italian enemies. Again he appeals to a strong German ruler.

The coronation of Otto I by Pope John XII in 962 marks a revival of the concept of a Christian emperor in the west. It is also the beginning of an unbroken line of Holy Roman emperors lasting for more than eight centuries. Otto I does not call himself Roman emperor, but his son Otto II uses the title - as a clear statement of western and papal independence from the other Christian emperor in Constantinople.

Otto and his son and grandson (Otto II and Otto III) regard the imperial crown as a mandate to control the papacy. They dismiss popes at their will and install replacements more to their liking (sometimes even changing their mind and repeating the process). This power, together with territories covering much of central Europe, gives the German empire and the imperial title great prestige in the late 10th century.

But subservience was not the papal intention in reinstating the Holy Roman Empire.

(Image of Otto I) Despite the dissension within the newly created Western Empire, the popes maintained the imperial organization and the imperial title, mainly within the Carolingian dynasty, for most of the 9th century. The emperors exercised little authority beyond the confines of their dominions, however. After the reign (905-24) of Berengar I of Friuli, also styled as king of Italy or ruler of Lombardy, who was crowned emperor by Pope John X, the imperial throne remained vacant for nearly four decades. In Italy, meanwhile, Roman nobles had usurped the political authority of the papacy. The East Frankish kingdom, or Germany, capably led by Henry I and Otto I, emerged as the strongest power in Europe during this period. Besides being a capable and ambitious sovereign, Otto I was an ardent friend of the Roman Catholic church, as revealed by his appointment of clerics to high office, by his missionary activities east of the Elbe River, and finally by his military campaigns, at the behest of Pope John XII, against Berengar II, king of Italy. In 962, in recognition of Otto's services, John XII awarded him the imperial crown and title.

Otto I the Great (23 November 912 in Wallhausen – 7 May 973 inMemleben), son of Henry I the Fowler and Matilda of Ringelheim, was Duke of Saxony, King of Germany, King of Italy

Papal decline and recovery: AD 1046-1061

The struggle for dominance between emperor and pope comes to a head in two successive reigns, of the emperors Henry III and Henry IV, in the 11th century. The imperial side has a clear win in the first round.

In 1046 Henry III deposes three rival popes. Over the next ten years he personally selects four of the next five pontiffs. But after his death, in 1056, these abuses of the system bring a rapid reaction. Pope Nicholas II, elected in 1058, initiates a process of reform which exposes the underlying tension between empire and papacy.

In 1059, at a synod in Rome, Nicholas condemns various abuses within the church. These include simony (the selling of clerical posts), the marriage of clergy and, more controversially, corrupt practices in papal elections. Nicholas now restricts the choice of a new pope to a conclave of cardinals, thus ruling out any direct lay influence. Imperial influence is his clear target.

In 1061 the assembled bishops of Germany - the emperor's own faction - declare all the decrees of this pope null and void. Battle is joined. But meanwhile the pope has been enlisting new allies.

In 1059 Nicholas II takes two political steps of a kind, unusual at this period, which will later be commonplace for the medieval papacy. He grants land, already occupied, to recipients of his own choice; and he involves those recipients in a feudal relationship with the papacy, or the Holy See, as the feudal lord.

This time the beneficiaries are the Normans, who are granted territorial rights in southern Italy and Sicily in return for feudal obligations to Rome. The pope, in an overtly political struggle against the German emperor, is playing a strong hand. The issue will be brought to a head within a few years by another pope, Gregory VII.

Gregory VII and investiture: AD 1075

Pope Gregory seizes political control by decreeing, in 1075, that no lay ruler may make ecclesiastical appointments. Powerful bishops and abbots are henceforth to be pope's men rather than emperor's men.

may make ecclesiastical appointments. Powerful bishops and abbots are henceforth to be pope's men rather than emperor's men.

The issue becomes known as the investiture controversy, being in essence a dispute over who has the right to invest high clerics with the robes and insignia of office.

The appointment of bishops and abbots is too valuable a right to be easily relinquished by secular rulers. Great feudal wealth and power is attached to these offices. And high clerics, as the best educated members of the medieval community, are important members of any administration.

In subsequent periods compromises are made on both sides, particularly in the Concordat of Worms, in 1122, where a distinction is made between the spiritual and secular element in clerical appointments. But investiture remains a bone of contention between the papacy and lay rulers - not only in the empire, after the first dramatic flare up between Gregory and Henry IV, but also in France and England.

Rome and the struggle for power: AD 1076-1138

The nine-year struggle between pope Gregory VII and the emperor Henry IV provides a vivid glimpse of the political role of the medieval papacy. St Gregory, canonized in the Catholic Reformation, is one of the great defenders of papal power. His career involves incessant power-broking and military struggle.

Henry IV, alarmed at the demands being made over investiture, sends a threatening letter to the pope in 1076. The pope responds by excommunicating the emperor. By his public penance at Canossa, Henry has the excommunication lifted. But the truce is short-lived. Henry's enemies, prompted by the pope's action, take a hand.

German princes opposed to Henry IV elect and crown, in 1077, a rival king - Rudolf, the duke of Swabia. Rudolf and Henry engage in a civil war, which Henry wins in 1080. By then the pope has recognized Rudolf as the German king and has again excommunicated Henry.

German princes opposed to Henry IV elect and crown, in 1077, a rival king - Rudolf, the duke of Swabia. Rudolf and Henry engage in a civil war, which Henry wins in 1080. By then the pope has recognized Rudolf as the German king and has again excommunicated Henry.

This time Henry's response is more aggressive. He summons a council which deposes the pope and elects in his place the archbishop of Ravenna (as pope Clement III). Henry marches into Italy, enters Rome and is crowned emperor by this pope of his own creation. Meanwhile the real pope, Gregory, is living in a state of siege in his impregnable Roman fortress, the Castel Sant'Angelo.

Gregory appeals for help to his vassals the Normans, recently invited by the papacy to conquer southern Italy and Sicily. A Norman army reaches Rome in 1084, drives out the Germans and rescues Gregory. But the Norman sack of the city is so violent, and provokes such profound hostility, that Gregory has to flee south with his rescuers. He dies in 1085 in Sicily.

Clement III returns to Rome and reigns there with imperial support as pope (or in historical terms as antipope) for most of the next ten years. Urban II, the pope who preaches the first crusade in 1095, is not able to enter the holy city for several years after his election. Unrest prevails in Rome, and uncertainty in the empire, until the Hohenstaufen win the German crown in 1138.